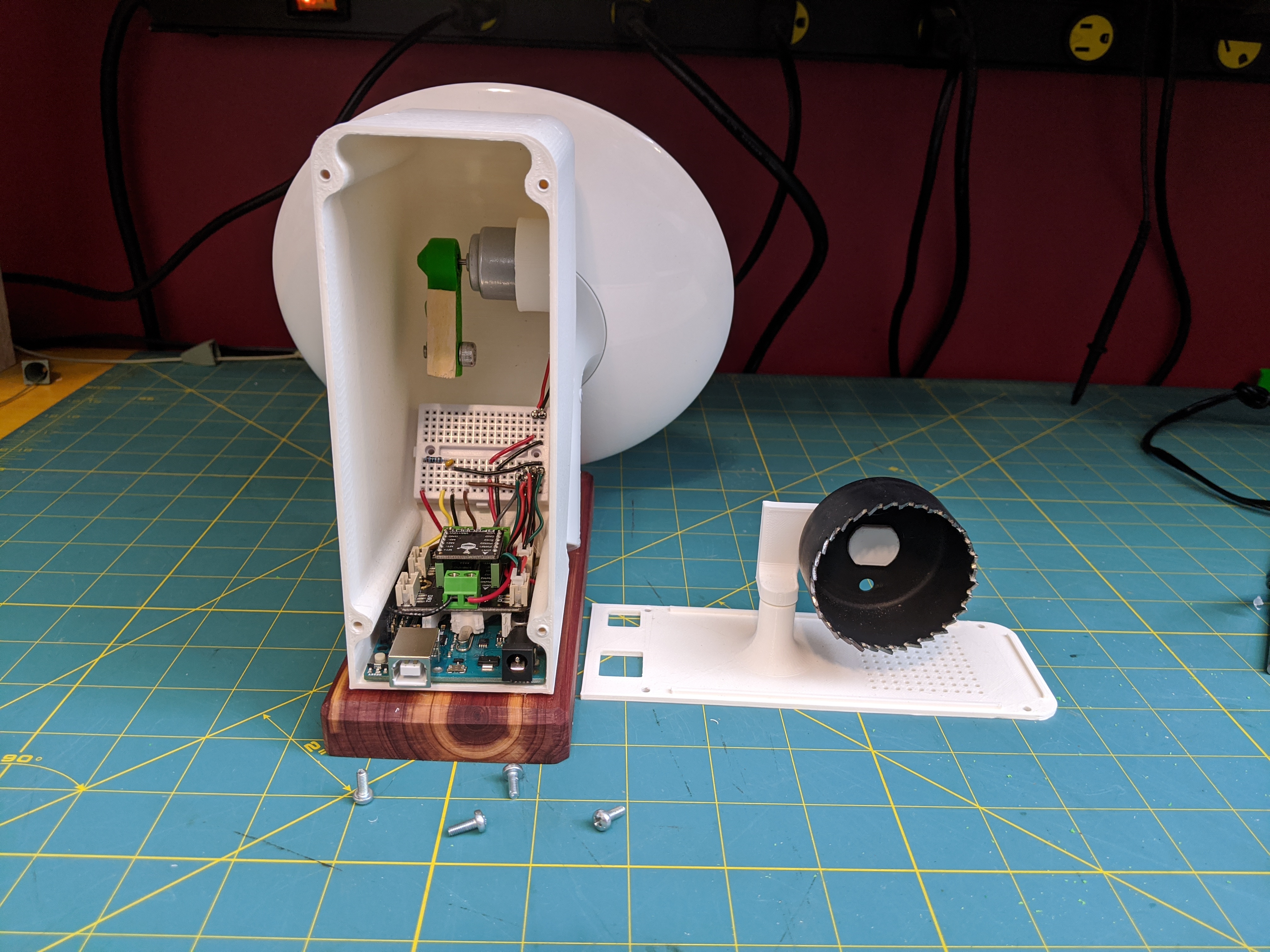

Historically, I have believed and argued that anthropomorphizing a machine is at best incorrect and at worst deceitful. Even now that I believe that stance to be misguided1 I have a hard time shaking a feeling of embarrassment when I admit to saying, “You did a good job today, little buddy,” while patting ORBiE on the head and turning him down for the night.

Today marked a few firsts: ORBiE’s first conference, my first public conversation about my art… and, strangely, a first admission that I feel gratitude toward a carefully-arranged few bits of plastic.

But he did do a good job today, and that deserves recognition.

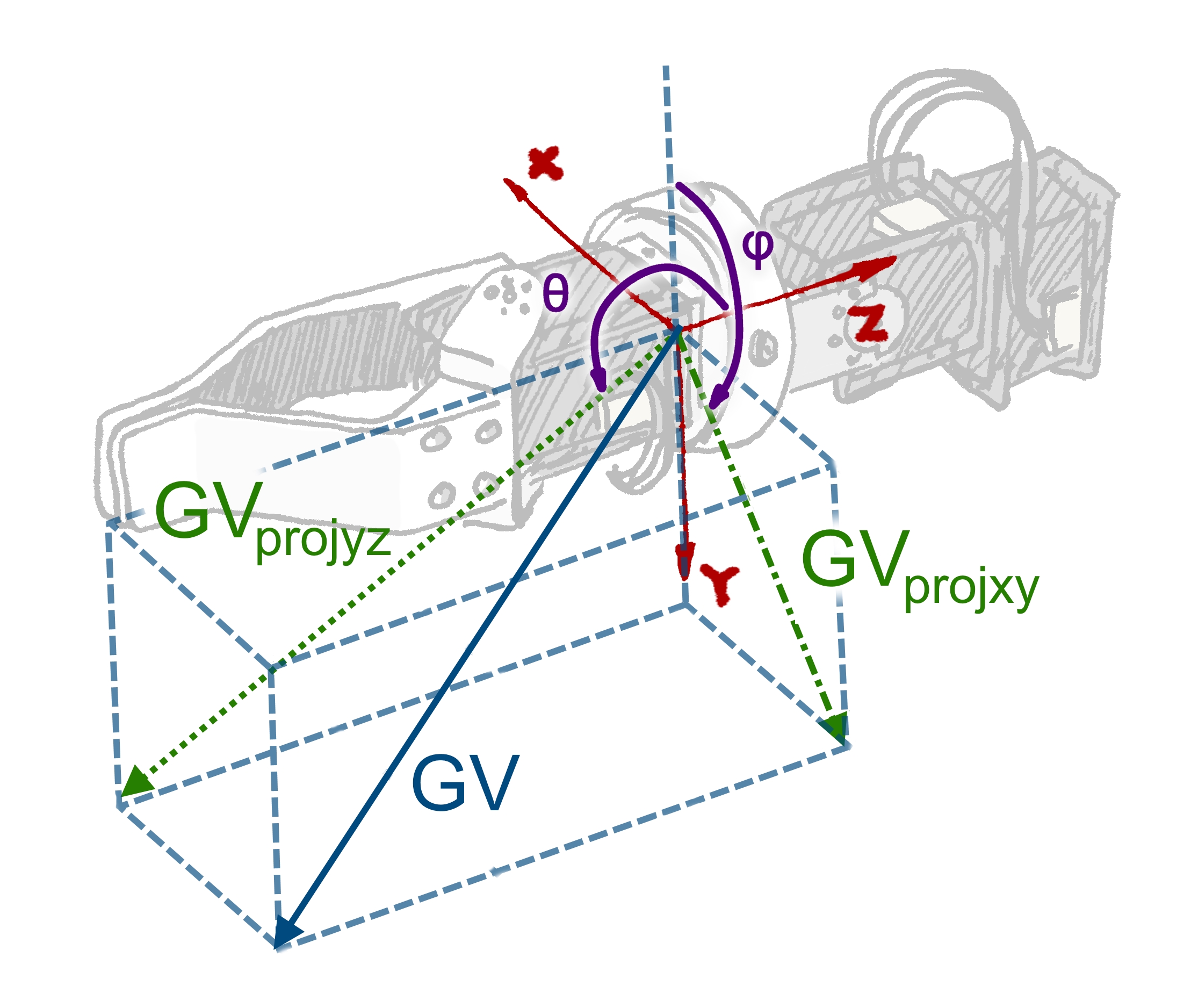

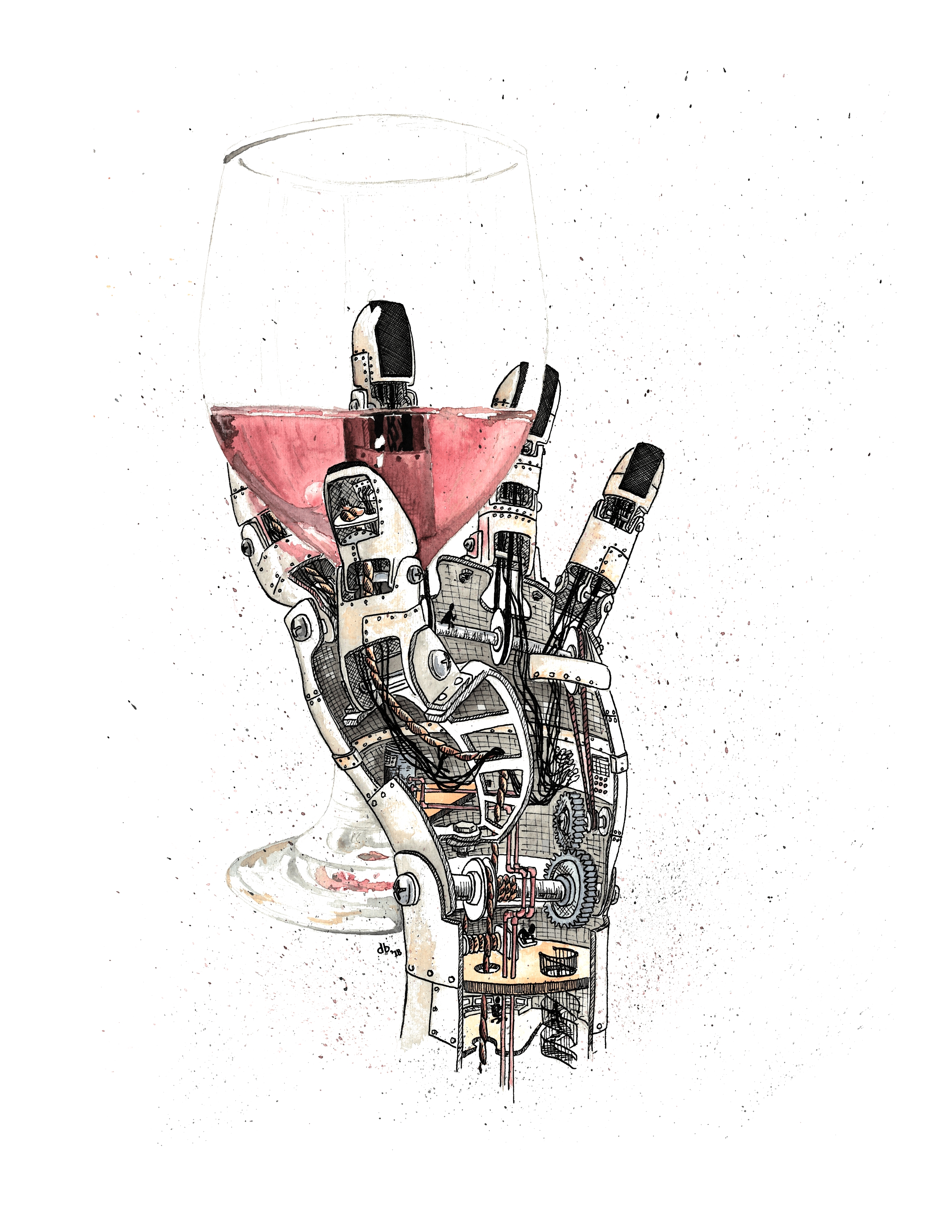

ORBiE and I attended2 the RISEx Conference as an artistic duo rather than in the typical engineer/project roles. Our interlocutors were curious and intelligent, and we talked for hours about art and robots3, engineering and ethics, human and AI relationships4, medicine and prosthetic technologies… all the fascinating, murky, and life-altering stuff that catches my attention.

I spent the day explaining to myself and others how it felt to try to build a meaningful relationship with plastic. We talked about how disappointing it has been to understand that all of the responsibility for meaning-making happens on my side of the fence. About my hopes that maybe if I were able to figure out how to have a real conversation things would feel different. About my concerns with the way economic and political systems influence model creation and access for the machines that I can have a conversation with, and my Turkle-seeded5 doubts about the relationships I could hope to build with them. I talked about open-source projects and democratic access to knowledge. I felt the people there share my hopes and my worries, offer their own stories, and light up when ORBiE waved at them. He may not have participated in the conversations to any great degree, but certainly played a role in starting them.

Another recent update to my model of the world has been a sudden awareness of research-creation: a method of knowledge creation that works in an equally valuable but very different way to scientific research. Even just the first few chapters of Natalie Loveless’ “How to Make Art at the End of the World” were enough to cause me to question my understanding of epistemology. “But how can creating art create knowledge?” I had thought, “It makes a record, or an artifact, sure… even emotion. But knowledge?” I had assumed that art was a process of communicating already-held knowledge from the artist to the audience, in a similar way to a scientist communicating the results of an experiment in a published paper. I even wrote a short poem about that back in 2023:

{science | art} is a process of thinking with all you’ve got to see what no-one else has, and then communicating what you’ve seen

{science | art} communicates that which {can | cannot} be said precisely

So far I think this holds up okay. But I had been imagining the process of “thinking with all you’ve got” to be fundamentally similar activities between the arts and sciences. I no longer believe that’s always the case6. In many successful artistic methods, there is an emphasis on lack of, loss of, or release of control, which is not typically welcome in engineering7. But in art, a dearth of control does not imply a dearth of rigour. The act of making, of performing, of dancing are artistic modes of thinking. Humans think through action. Action takes place in all kinds of settings–not just those that are well-controlled8. So I’d like to propose an update to the poem9:

{science | art} is a process of thinking with

all you’ve gotyour whole {mind | body} to see what no-one else has, andthencommunicating what you’ve seen{science | art} communicates that which {can | cannot} be said precisely

To more clearly state one possible answer to my rhetorical question earlier: “how can research creation create knowledge? “By facilitating conversation. So thanks ORBiE, you did a good job today.

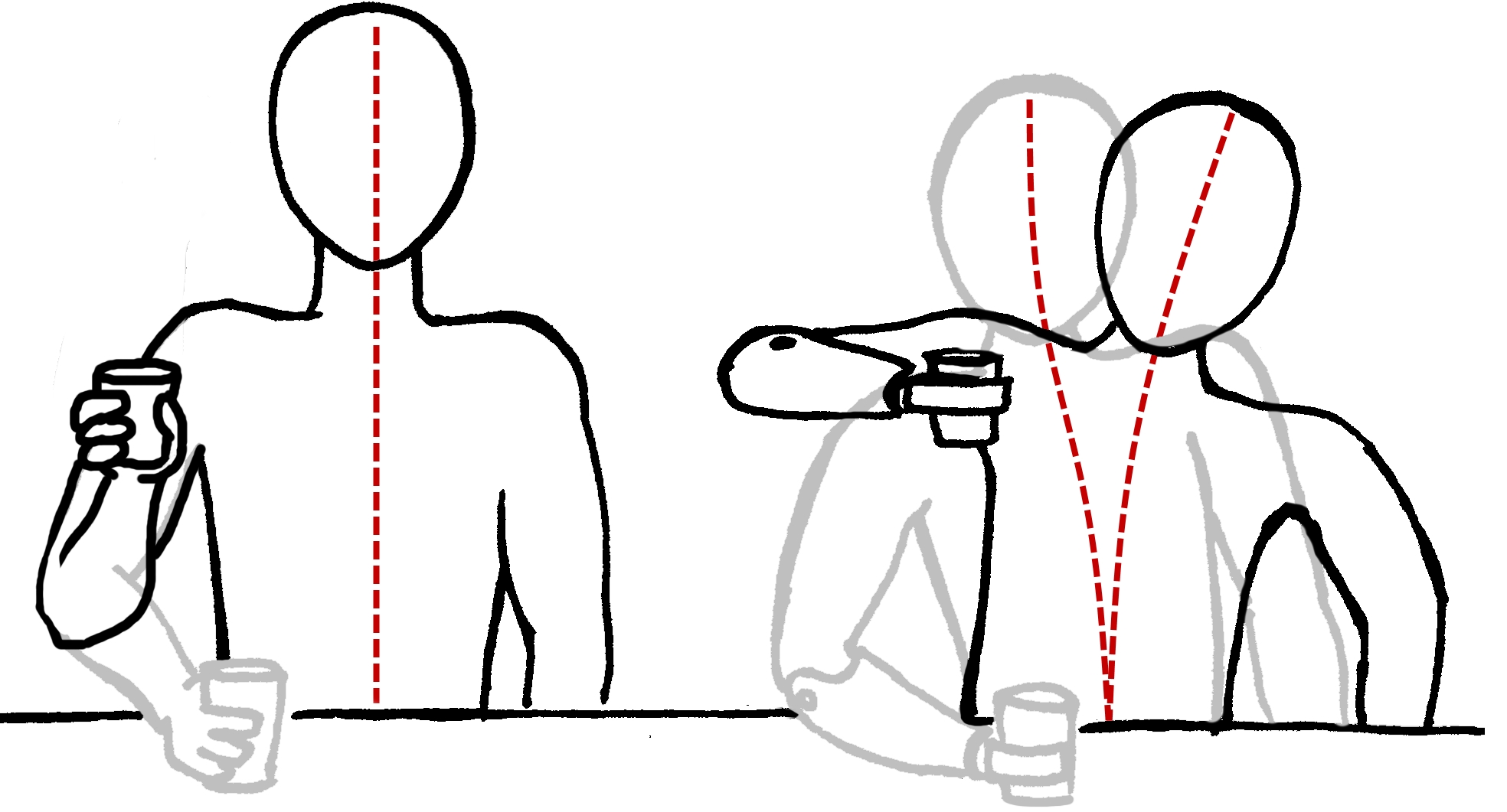

- Explicitly, my gut feeling is that humans are hard-wired to anthropomorphize non-human things, making the avoidance of anthropomorphization at best impossible and at worst deceitful. As an example for yourself you can draw two ovals close together anywhere on the top half a circle. You’ve drawn not just a recognizable face but an entire character. Doing the same exercise with a triangle yields a different character. We anthropomorphize ink on paper without a thought, but somehow I had considered anthropomorphizing more animated forms childish. The anthropomorphization is inevitable; its ethical handling depends on that acknowledgment and an understanding of its practical boundaries. ↩︎

- Thanks.to the Institute for Smart Augmentative Rehabilitation Technologies for sponsoring my ticket to the conference. ↩︎

- Great examples of contemporary artists using robots as art rather than just to create art include: Marco Donnarumma, (artist, inventor, and theorist who uses dystopian prosthetic robots to confront normative body politics), Arthur Ganson, Jakob Grosse-Ophoff, and Zimoun, who use machines to create poetic expressions of human experiences, and PCZ, an artist collective which hosted a fascinating ritual of friendship for their robotic companion in the maple forest of Mont Royal, complete with tin foil hats (see pages 115-116 of their zine). ↩︎

- Some great reads here include Sherry Turkle (see next footnote), James Bridle’s “Ways of Being” (2022), and Alač et. al’s “Talking to a Toaster” paper (2020). ↩︎

- Sherry Turkle, “Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other“, 2011 ↩︎

- The artist that had me thinking this might be the case is David Lynch, whose process I find very conducive to the sciences. So at least in his case, there’s some overlap. ↩︎

- There, even uncontrolled variables are modelled with distributions so as to be predictable, and thereby controlled for. ↩︎

- As Joseph might say, “free the robots!” ↩︎

- I find it amusing that this seems to suggest considering Science a subprocess of Art, as mind is to body. ↩︎