A true story. April 4, 2018

I sat down in the back of the bus today, just like I always do. I was in a good mood, and feeling like I might want to chat with the other commuters, so I sat upright with open body posture. I’ve never actually started a conversation with anyone on the bus, because I’m too concerned about respecting boundaries, and I’m never sure whether anyone else actually wants to talk to me. I’m usually open to having a conversation though, and I’ve found that something in my face or the way I sit must signal to other people that I’m open to it, because occasionally they’ll strike up a conversation—and it’s almost always interesting.

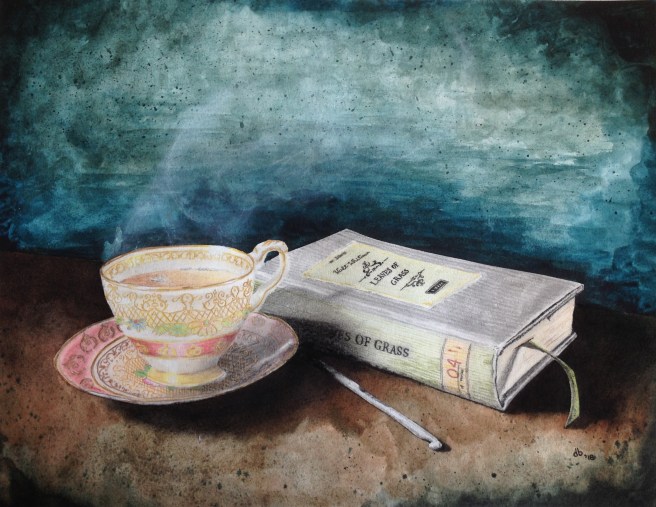

I had just received back a drawing I had done for the Engineering Art Show, and I held it face-up on my lap as though that were the most natural way to transport it, so that it could serve as a conversation starter for someone else should they choose to use it. Beside and to the left of me a few seats away sat a First Nations woman who looked to be in her mid-forties. She wore a pink sweater that seemed like it had seen quite a lot of use, white and black checkered pants, and sneakers that at one time had been white. On the seat beside her was a clear plastic garbage bag, inside of which were a few empty water and pop bottles, and what might have been a change of clothes. She had her right leg crossed over her left knee, and both her hands were continually employed in pulling her foot up closer to her waist as it slid toward the ground.

She pointed at the drawing on my lap, and asked,

“Did you draw that?”

“Yes, I did,” I replied, always happy to receive recognition from strangers.

“What is it?” she asked. I was a bit taken aback, as I had thought that was relatively clear by just looking at it. In my head ran an image of a five-year-old child, pleased as punch with a drawing he had made that no one else could recognize. I turned the picture toward her so that she could see it better, and started to explain what I had drawn.

“It’s a drawing of a robotic hand I designed, shaking hands with a human to symbolize the equal partnership between robots and humans we should see in the future.”

“Oh,” she replied, “It’s very beautiful.”

“Thank you.” I sat back, she sat back, and that was the end of that conversation.

A while later down the road I happened to glance again in her direction and noticed that her face was buried in her sweater, and she was muffling sobs. My face must have had a look of mixed surprise and concern, because the man sitting next to her saw my expression and turned to look at her. He was equally concerned, and put a hand on her shoulder asking her if she was okay. They talked for a few moments, but I couldn’t make out any of what they said. She spoke in very timid tones, just barely audible over the whir of the bus engine.

After a while their conversation was over too. I thought to myself, trying to guess at what the problem might be, and whether there was anything I should do to help her. It seemed as though I should say or do something, but also that it wasn’t my place. I started to think about the social constructs around strangers talking to strangers; what was allowed and what was not allowed, why, whether that was good or bad, and if it needed change how someone might try to do that. Of course, I was barred by my own inability to initiate conversation.

Some moments passed, and she spoke to me again, pointing at the picture.

“You know what that makes me think of?” she asked, as timidly as before.

“What?” I asked, moving one seat over so I could hear her better. It seemed like she needed someone to talk to.

“The Terminator.” She grinned from ear to ear, her eyes disappearing as she chuckled. It was not at all what I wanted to hear, since I’ve built up the Terminator for myself as a societal hurdle we need to get over before we can really move forward in humanoid robotics. I laughed a little with her, then replied,

“Well, I hope the robots in the future are a little nicer than that!” She smiled and nodded. She was only joking after all.

“I think I’m a robot,” she said, not joking this time. Her dark, wet eyes said she was hinting at something a little bit more.

“Why do you say that?” I asked, leaning in to hear better. She looked down at her hands concernedly, as though they weren’t hers. She flexed and unflexed them, splaying her fingers. There was a tattoo of some symbol I didn’t recognize on the back of her left hand.

“I’m a science experiment.” Her voice had a quality of unbearable sadness, like she had made some great mistake she couldn’t fix. I looked at her, confused. Was she suggesting that she was a subject in some drug testing trials? Maybe her own? She said a few more things that I was unable to hear over the sounds of the bus as it left South Campus.

“Why do you say you’re a science experiment?” I asked. I’m not sure what I was hoping for, perhaps to find the reason for her sadness and maybe a way to console her. She pointed at her face.

“Do you see me?” she asked. It looked like she was indicating the fact that she was Native American. I was suddenly painfully aware of the common societal perception and historical treatment of First Nations people, and the fact that only a moment ago my own mind had jumped to the conclusion that she must be on drugs. I wasn’t sure what to say. We sat in silence for a short while. Eventually, I replied,

“You seem fairly human to me. I’d say you’re more than some science experiment, more than some robot.”

She said something again that I couldn’t hear. Her voice was so soft.

We sat again for quite some time without talking. During this time I felt sure that I was there for some reason; I was supposed to say something or do something for her. What did she need?

A while later she spoke again.

“Which one’s the robot?” At first I was confused, then realized she was referring again to my drawing. Then I was confused again; I had thought it was pretty obvious.

“Well, this one,” I replied, pointing at the robot hand in the picture.

“Why do you think that’s the robot? What do you think of when you think of robots?”

“Well, because that’s the one I designed; it’s made of plastic and metal, and sensors and stuff,” I was having a hard time gauging her level of understanding. Finally I clued in that she was talking big-picture. “But…” I thought for a moment, “People tend to think of robots and humans as separate things. That one’s lesser than the other.” I was trying to make a connection back to her feelings about her ethnicity. “But I think… I mean… I hope, in the future, that there won’t be a distinction anymore. I mean, if a thing can think for itself, and if it’s got feelings, then it ought to have the same rights as any other human.” She nodded. She must have picked up on my analogy. Maybe I was helping her?

“You know, I’ve met a lot of robots,” she said.

“Oh?” I asked, “Which ones?” Maybe she knew someone who owned a Roomba or something.

“No. I don’t like to name names.” I nodded as though I understood, but it was another block or two down the road before I did. She was talking about people, about connections. I thought back over our entire conversation, and how she must have had the human condition in mind the whole time while I was talking shop about machinery. I was right, I was meant to be here, having this conversation—but it wasn’t for her, it was for me.

A question entered my mind, but I wasn’t sure I wanted to know the answer. I initiated the conversation this time, for the first time.

“Do you think I’m a robot?”

“Yes,” she replied, without hesitation. She smiled like she had done with her Terminator joke.

“What makes you say that?” I asked.

“Because you draw them. And you believe in them.”

I nodded. With that, my stop was up and I had to get off the bus. I thanked her for the conversation, and we parted ways.

od, that when glued and screwed together create the cutouts necessary for all the pieces to fit in properly. Both the harmonica and USB stick are held in place using friction fits, which actually turned out remarkably well given my limited experience with woodworking projects. If you’re planning on making your own watch or something similar, I recommend cutting your pieces very slightly larger than required and sanding down, testing the fits as you go until you’re satisfied.

od, that when glued and screwed together create the cutouts necessary for all the pieces to fit in properly. Both the harmonica and USB stick are held in place using friction fits, which actually turned out remarkably well given my limited experience with woodworking projects. If you’re planning on making your own watch or something similar, I recommend cutting your pieces very slightly larger than required and sanding down, testing the fits as you go until you’re satisfied.