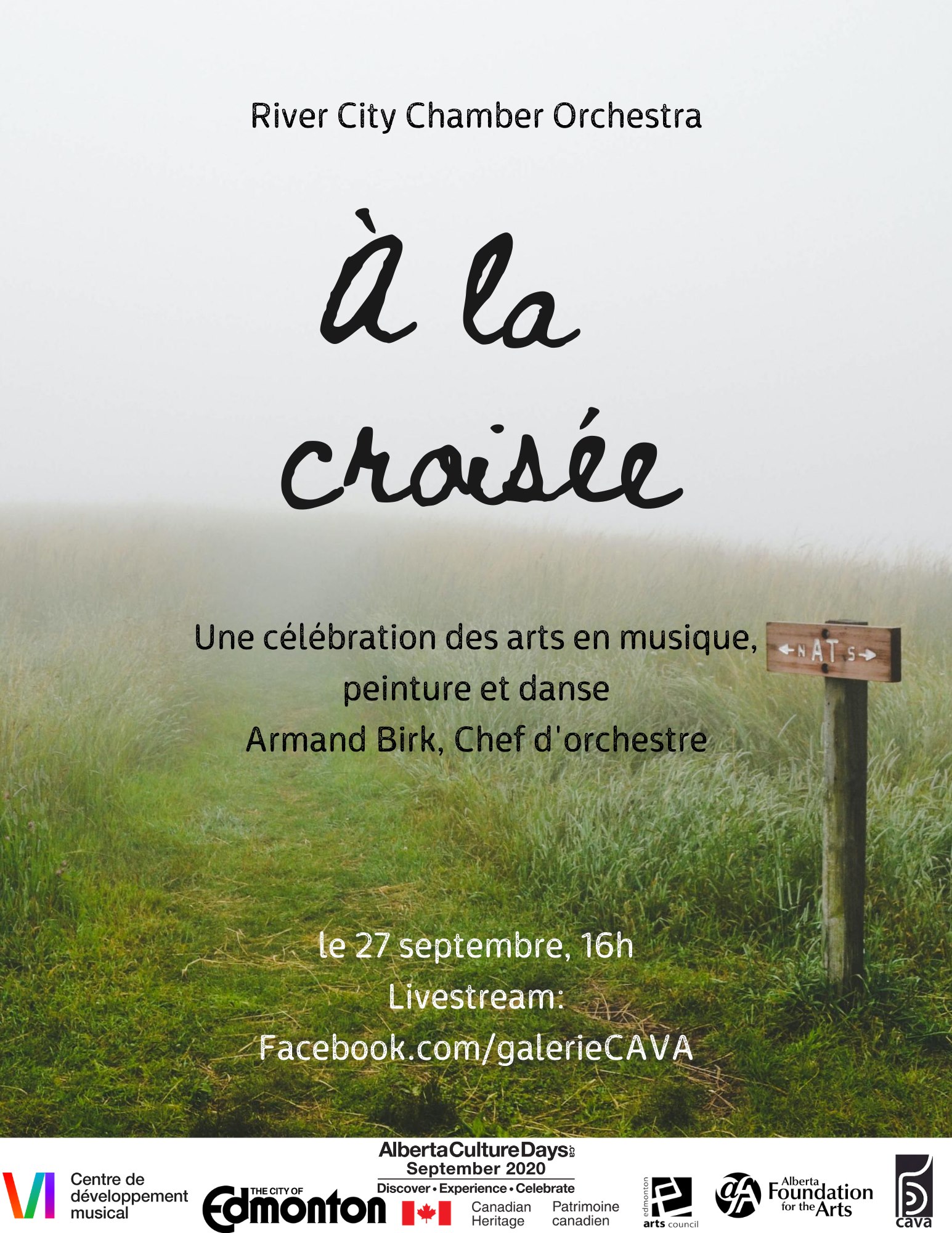

Note: This article describes an event that is now passed. To view the painting that resulted from this performance, click here.

| I have the opportunity to perform a live painting, grâce à la galerie CAVA! The River City Chamber Orchestra, conducted by Armand Birk, will provide “exciting and emotionally satisfying” sounds from Rameau, Vivaldi, Finzi and Tchaikovsky; the dancers are ready to deliver energetic and dynamic performances; two other artists and I will express ourselves with paint and brush. The livestream will take place on September 27 at 4 p.m. UTC-06. | J’ai l’occasion d’effectuer une peinture en direct, grâce à la galerie CAVA! Le River City Chamber Orchestra, dirigé par Armand Birk, fournira des sons «excitants et émotionnellement satisfaisants» de Rameau, Vivaldi, Finzi et Tchaikovsky; les danseurs sont prêts à offrir des performances énergiques et dynamiques; deux autres artistes et moi nous exprimerons avec de la peinture et du pinceau. Le livestream aura lieu le 27 septembre à 16 h. UTC-06. |

Preparing for a live painting has been an interesting experience, and I’ve had some insights along the way that I’d like to share with whoever’s interested.

When painting becomes a performance art, the process becomes part of the expression.

Typically we think of a painting as a very different endeavour from an orchestral concert, or a dance performance. One of the main reasons is that you only ever see the finished product, and there is very little (if any) temporal aspect in the way that you take it in. Listening to a concert or watching a ballet necessarily takes time, and during that time the performer can take you through a range of emotions. Each movement might tell a different story, and contain different themes, and only by taking them all in turn can you get the full effect the performer was going for. With a painting however, this usually isn’t possible. You see the whole canvas at once, and the artist isn’t there to reveal it to you in any particular way. But when the viewer is there for the creation of the painting, a whole host of new opportunities arise.

Artistic expression through performance is dependent on planning and practice.

I’ve done enough performing in my lifetime (though this is my first live painting) to know that you don’t just show up on stage and wing it. Typically, the people that are able to cooly improvise really well have spent an incredibly long time practicing and becoming comfortable both on stage and with their medium. Certainly, the jokes or the saxophone licks might be improvised on the spot, but you can be sure this isn’t the first time they’ve ever improvised.

I’ve been playing recently with a more improvised style, which I feel would be both fun to perform and fun to watch. But the nature of this style of painting is that you’re not sure how it’ll turn out. This is where the preparation comes in. I’ve spent the last few weeks turning over ideas, sketching things out, planning the composition, trying out colours, crafting stencils… Generally doing whatever I can to make sure that once I’m on stage I can just throw paint at the canvas (literally) and have a reasonable chance of having a good painting at the end.

Which reminds me… I need to find those drop-cloths.

Planning and practice are also good for refining ideas.

This painting has evolved a lot from first conception to what it will actually be on September 27. Usually when I have an idea that I’m excited about, it makes it onto the canvas in a few hours or days. But this time I’ve had to hold off and be patient—and since I’m carefully planning and practicing, I’ve been thinking about it a lot. I’ve developed a few themes that I’m hoping the finished painting will convey (and that the process will be a part of expressing):

- The interplay between free-form improvisation and careful planning

- Similarities between painting and performance arts

- Colours and shapes can be thought of as similar to instruments in an orchestra. Each plays their part, which alone is beautiful but quite abstract; together they paint a complete picture that expresses the composer’s vision

- Each performance is invisibly supported by centuries of human innovation and artistry

- Seeing not only the performance, but also understanding all of the human effort that went into making it possible lends additional luminance to the art

We never work alone.

Even when I’m at home alone playing the piano, my artistry depends on other people. I depend on composers and performers that shaped musical theory and style, inventors that iterated on instrument design, scientists that discovered the physical principles that make them work, even the various political and societal structures that afforded these people the opportunity to do the work that they did.

Artists (of any kind) work to make the world a more beautiful place. Whether or not we work with other people, we never work alone. We’re only the end of this lineage so far.