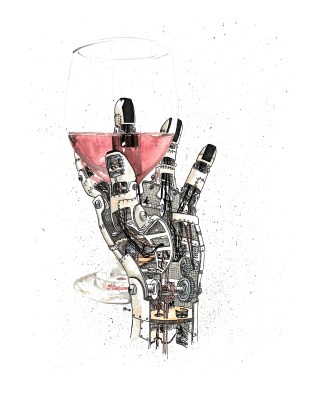

I’ve been saving this one up for a while… and it’s finally finished! An automatically levelling wrist to help reduce movement compensation in people who use prostheses:

There are a lot of details about how this device works and what effect it actually has on compensatory movements in my M.Sc. thesis that I don’t have the space to include here. For those of you not looking to casually browse a 105-page technical document, I’ll give you the quick run-down:

Motivation

Anyone who doesn’t have a fully-functioning wrist is forced to use the rest of their body to compensate for the lack of movement there. For people who’ve suffered from an upper-limb amputation, this constant compensation can lead to strain injuries in the back, shoulder and neck.

Commercially available prosthetic wrists don’t have enough degrees of freedom (and are generally quite difficult to control), making it nearly impossible to lift something to a high shelf while keeping it level. Allowing the prosthesis to take care of some of the control burden and keep the hand level on its own might be able to get rid of some of these compensatory movements.

How the Levelling Works

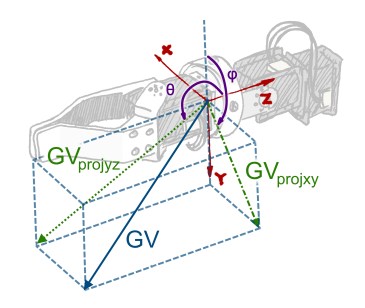

The secret ingredient is the addition of an inertial measurement unit (IMU) in the base of the hand. This sensor can tell which direction gravity is pointing, and gets the angles φ and θ. The control computer then uses two separate control loops: one that keeps the rotation angle φ =180°, and another that keeps θ to whatever angle the user sets.

Does It Help Reduce Compensation?

We did a study with 12 able-bodied people wearing a simulated prosthesis in a motion-capture environment, testing on two well-documented clinically-relevant tasks. One had a significant vertical component to it, while the other had motions mostly in the horizontal plane.

The brief summary is that we found that an automatically levelling wrist may reduce compensatory movements in shoulder flexion for vertically-oriented tasks, but doesn’t provide a statistically significant benefit on horizontally oriented tasks. Through performance metrics and user satisfaction surveys, we also determined that the reliability of an automatically levelling wrist is a major design criterion to consider for future research in this area.

od, that when glued and screwed together create the cutouts necessary for all the pieces to fit in properly. Both the harmonica and USB stick are held in place using friction fits, which actually turned out remarkably well given my limited experience with woodworking projects. If you’re planning on making your own watch or something similar, I recommend cutting your pieces very slightly larger than required and sanding down, testing the fits as you go until you’re satisfied.

od, that when glued and screwed together create the cutouts necessary for all the pieces to fit in properly. Both the harmonica and USB stick are held in place using friction fits, which actually turned out remarkably well given my limited experience with woodworking projects. If you’re planning on making your own watch or something similar, I recommend cutting your pieces very slightly larger than required and sanding down, testing the fits as you go until you’re satisfied.